The creation of a Tumblr account in seventh grade quickly blossomed into an addiction of scrolling my dashboard every morning and late into the evening. Among the early 2010s hipstercore of galaxy print, triangles, and gifsets from the Vincent Van Gogh episode of Doctor Who, I found blogs whose owners were farther into their tormented teenage years than I. It was through them I discovered the name that would more or less carry me through the next decade of my life as a writer, woman, and student. Sylvia Plath.

I spent my middle school years at a charter school. Classes were small, privacy low, emotions high. Paramore’s Riot! album was a fixture on my purple iPod Nano, and my fingernails were often painted black. The last thing I needed to add to my melodrama was a copy of The Bell Jar, yet when I called my mother one day while she was at work and asked her to bring a copy home for me, she obliged.

**

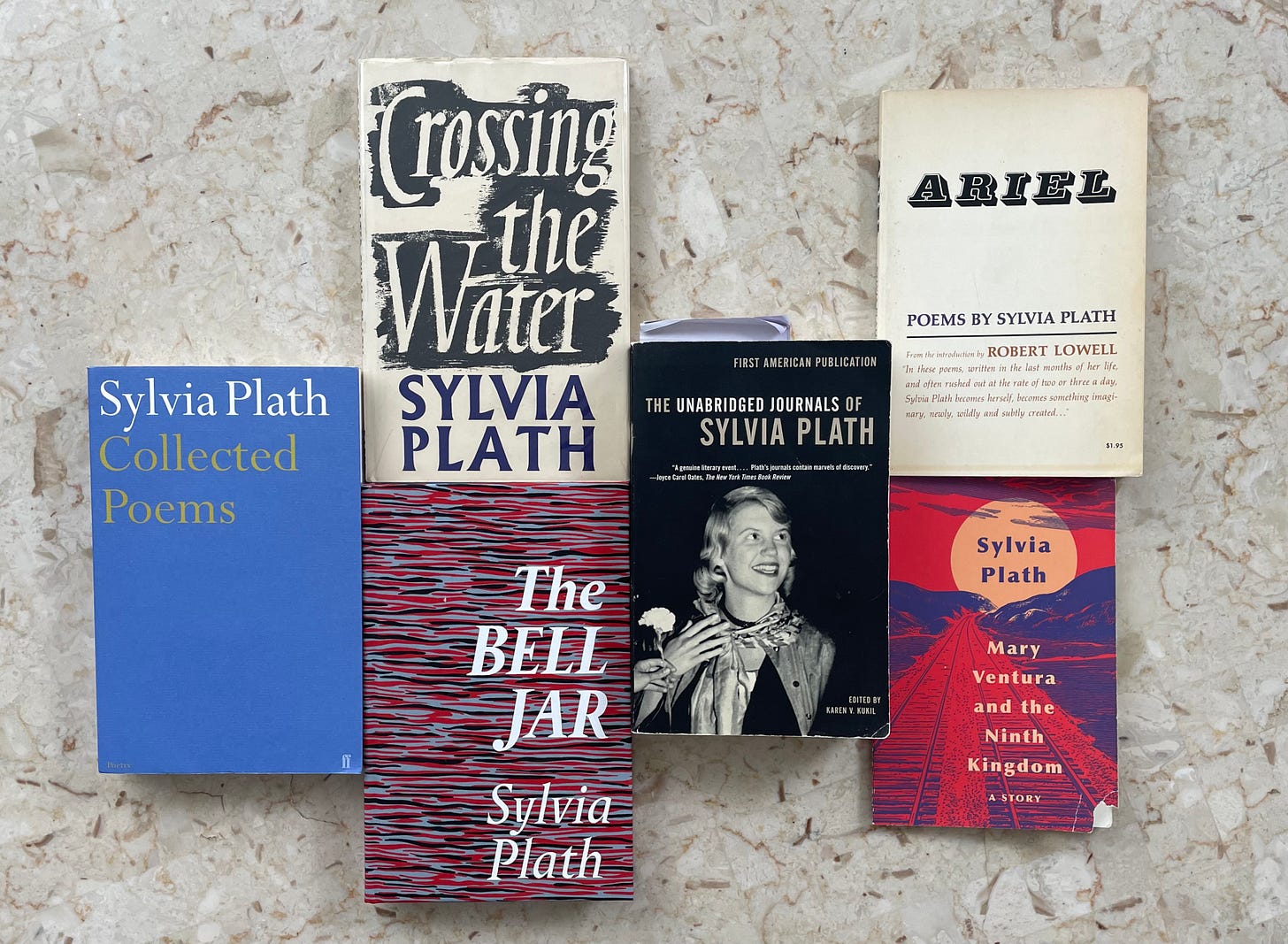

By sixteen, I had claimed “Elm” as my favorite poem from Ariel and seen the 2003 film Sylvia, starring Gwenyth Paltrow and Daniel Craig, multiple times (to this day I’m still baffled at its 37% rating on Rotten Tomatoes). During my senior year of high school, I opted to work on Election Day and brought The Unabridged Journals with me to my 14-hour shift. As I checked people in to vote, an older gentleman gestured towards my reading material. “Don’t read that,” he said, his tone jovial. “You’ll get depressed.”

Admiring Sylvia Plath is a double-edged sword in the eyes of contemporary media and its consumers—there is intensified empathy for her short life and lost potential on one end, and the fetishization of a dead woman on the other. My years-long fascination with her has been met with skepticism that borders on fear-mongering. One is not seen reading Plath—rather, she is caught. Despite the legions of fans who will defend her, spend years researching her—ignorance (i.e., a hard-to-crack stigmatization of mental illness) often overshadows a legacy of literary talent and relatability.

**

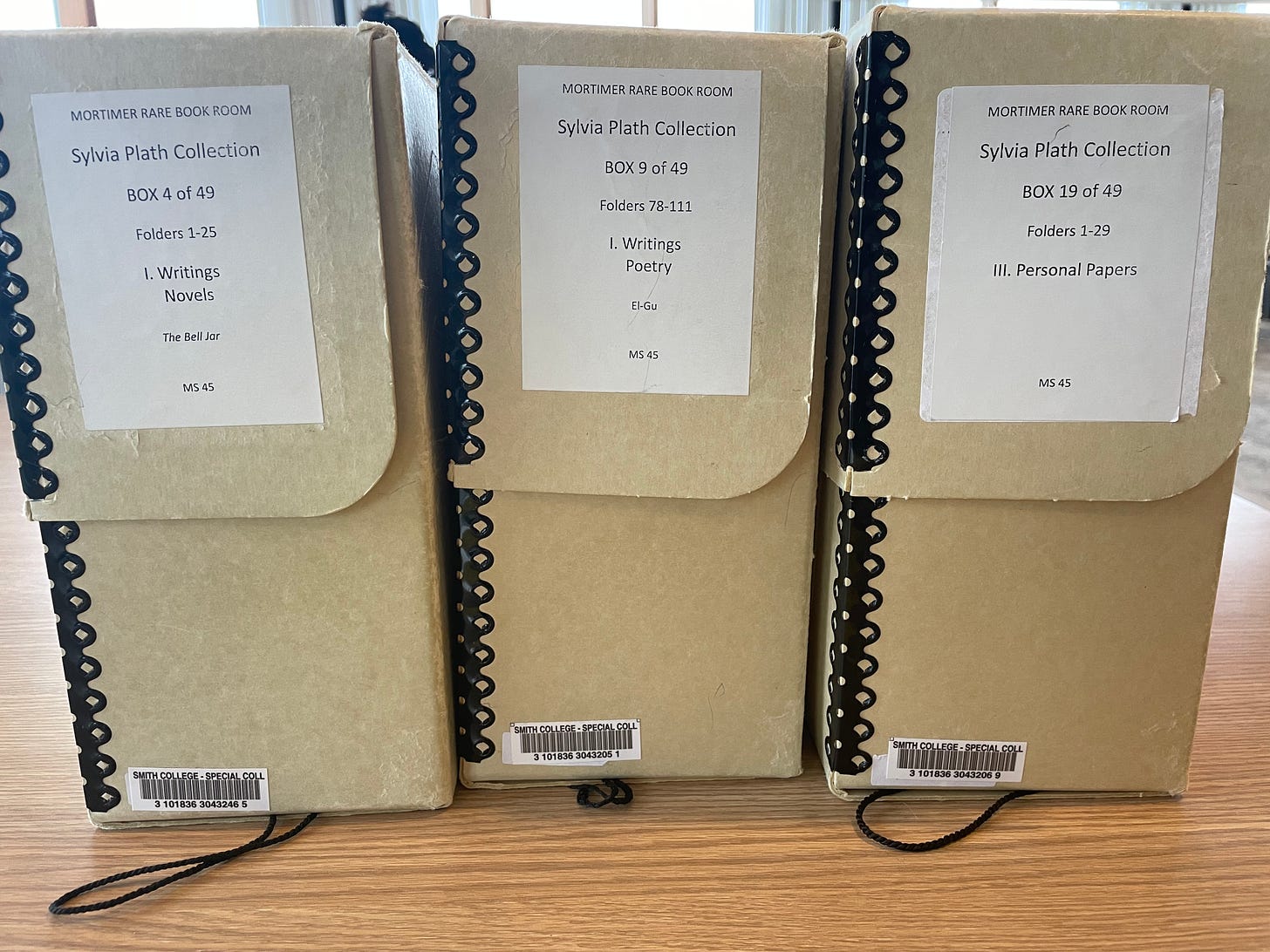

Last summer, I was presented with the unique opportunity of visiting Northampton, Massachusetts, the home of Plath’s alma mater, Smith College. On my one free day of the writing conference I was attending at UMass Amherst, I had chosen to go to Smith. The Mortimer Rare Book Room at Neilson Library houses boxes of Plath’s papers, manuscripts, and personal artifacts by the dozens.

**

I thought the Mortimer Rare Book Room was a museum at first, that had manuscripts on display behind glass cases. My naïvety revealed itself when I discovered that I had to sign in at a desk, place my bag in a locker, and wear a badge on a lanyard around my neck. I walked through the glass doors and was given another form to fill out, along with three call slips.

State the reason for your visit today, the form instructed. At a loss for words, I wrote “Personal research.” Partially true, but I felt like an intruder. My dedication was far from the ranks of Emily Van Duyne and Heather Clark, Plath scholars who have dedicated literally years of their lives meticulously studying hers. (Red Comet, Clark’s 1200-page beast of a Plath biography, was a 2021 Pulitzer Prize finalist and took eight years to complete).

**

I gave myself an hour. I was diplomatic with my choices when it came to the 49 boxes from the archives. Soon enough, I was holding pink-papered drafts of poems (including "Elm” and “Fever 103°”) covered with Sylvia’s scribbles, and looking through the Letts Royal Office Tablet Diary she kept the last full year of her life (1962). It was overwhelming, sentimental, and eerie all at once—I was fulfilling a dream I didn’t know I had until that moment. How many starry-eyed girls had been in this room before me, looking for remnants of Sylvia’s personhood?

Perhaps we would never know of these things existing if she hadn’t been marked by tragedy. I noticed that her mother, Aurelia Plath, had donated most of the contents of Smith’s collection decades after Sylvia died, in the 1980s.

She’ll be 30 forever, unlike Joan Didion, who died at the age of 87 in 2021. A spectacle was made of Didion’s death, but we are only at the beginning of it. Last November, 224 of Didion’s personal items went up for sale at a bloodbath of an auction that generated more than $1.9 million.

Fascination can rot as quickly as it becomes ripe. When I started to take writing more seriously, I clung to someone so famous because I didn’t know any better. Sylvia Plath represented all the things I wanted to be but couldn’t. A penchant for confession who could eloquently express her fear of mediocrity and desire for success. A woman of her time, who still dared to want more than what was expected of her—a life outside of domesticity. But at the core of her body of work was someone who longed to be understood—something that can seem nearly impossible to achieve, however rich our inner lives may be.

Our memory of her is up for interpretation. Among the posthumous accolades there are memes, Tweets, Etsy stores, and the like (of which I’m sometimes a willing participant). The metaphorical fig tree passage from The Bell Jar was brought to life (and further popularized) in Aziz Ansari’s Netflix show Master of None.

Despite my afternoon at Smith, I will never truly know her, even in hypotheticals—dream dinner party guest scenarios and all. We only have her past, and mourn what could have been. While history does have a way of revealing itself, I’ll leave the extracting from the margins of her life to the professionals.

There is one thing I’m certain of—we’re lucky to have Sylvia, and the people who care for her regardless of their proximity.